Table of Contents

Introducing the

Introducing the

FOLK PLAYS of ENGLAND

Ron Shuttleworth.

1984/2011

Author of

“So You Want to Start Mumming”

“Constructing a Hobby Animal”

WHAT is this book about.

WHICH plays are Folk Plays.

WHEN was it performed.

WHO used to do it.

WHO does it now.

WHY they did it.

WHERE was it performed.

WHAT they wore.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

I think that people have a right to know what qualifications an author has in his subject. On paper I have none and any expertise comes from experience gathered over eighteen years with an all-year team called Coventry Mummers and an interest which has led me to seek to acquire everything that has been written about the Folk Plays [rash fool!]. I have tried to differentiate between opinion and fact and to give as complete and balanced a picture as space will permit. How successful I have been is for the reader to decide but, in the words of a Mummers’ song, I can say “I have done the best I can, and the best can do no more.” RKS. 1984,2018.

WHAT IS THIS BOOK ABOUT?

“We open the door, we enter in.

We hope your favour we shall win

Whether we rise or whether we fall

We’ll do our best to please you all.”

[Presenter’s Lines]

In the following pages it is hoped to answer the sort of questions about folk plays which are most often asked by members of the public. If some of the replies seem to be full of ‘maybe’ and ‘perhaps’ it is because there are hardly any written accounts more than 300 years old. This may only be because those who could write did not consider the Play worth recording, but it means that to go further back involves a lot of guessing, helped by comp-arisons with other traditional customs. As with most areas of folk-lore and custom, beware of neat, water-tight theories with no loose ends – they are probably too good to be true.

Imagine that all the customs, legends and traditions of the various peoples and ages of this country were represented on nearly transparent sheets. These sheets are then stacked in order with the earliest at the bottom, and we have to interpret by looking down through the stack. Some items will be seen clearly, but others will be altered, coloured or distorted by those above or below. Anything which cannot be proved must be left open to question.

As both the performance of a custom, and its meaning for the participants can change from place to place and from age to age, it is often important to define time and location when offering possible explanations. This study will concern itself mainly with plays in England.

The folk play has attracted a large amount of scholarship and this booklet has to try to steer a course between triviality and overkill. There are areas which only get a sentence or two and which really rate a chapter at least. Anyone who recognises this and deplores it should realise that this book was not written for them.

WHICH PLAYS ARE FOLK PLAYS?

“Activity of Youth. Activity of Age

The like was never seen before on any common stage.”

[Presenter’s lines]

“We’ll show you Sport and Pastime before we go away.”

[Iping, Sussex]

In the past these plays were usually called after the local name for the performers e.g. Mummers’ Play, Plough-Boys’ Play, etc. A scholastic term is “Ritual Drama” but “Folk Play” is chosen here as being most readily understood by the most people.

Although the texts and content differ widely from place to place, the basic plots of each type of play vary little and it is possible to recognise certain basic actions common to all. Someone is ‘wounded’ or ‘killed’ and later restored to health and life. It is also general that the spectators shall reward the players with food and drink and/or money.

There are three basically different types of English Folk Play:- the Sword Play, the Wooing Play and the Hero-Combat Play.

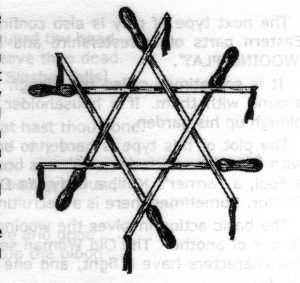

The SWORD-PLAY is associated with the Longsword Dance which is found mainly in Yorkshire. In this dance six or eight men, each with a strip of metal or wood about three feet long and called a ‘sword’, form into a circle by each holding the point of his neighbour’s sword in his free hand Like this they then perform various intricate manoeuvres which climax with the swords being woven together to form a ‘lock’ to be held up and paraded by one of the men.

One variation of a ‘lock’ which is also the badge of the English Folk Dance and Song Society.

One variation of a ‘lock’ which is also the badge of the English Folk Dance and Song Society.

The action of the Sword Play goes something like this:- A Clown or Fool acting as Presenter comes on and requests leave for the players to enter, and room for them to perform. He brings on the Captain or King who then “calls on” the other dancers with a song which describes the supposed virtues of each. After a dance there is either a general mêlée in which someone is killed, or, the King argues with the Fool and calls upon the dancers to help him and a lock is formed about the neck of the Fool, the swords are drawn suddenly away and the Fool falls ‘beheaded’. In turn, the dancers deny involvement and each accuses the man next to him. Eventually the corpse is returned to life – sometimes without the doctor deemed essential in the other types of play – and the performance concludes with another dance.

“Six finer swordsmen ne’er stood here. And proud of it are we.” [calling-on song

Beheading the Fool,

There are really very few complete Sword Play texts, although many playless sword- dances show traces of having had a play in the past.

The next type of play is also confined to a definite area – Lincolnshire and the Eastern parts of Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire – and is usually termed the ‘WOOING-PLAY‘. It is sometimes called the Plough Play because the teams might drag a plough around with them. If a householder was stingy it was not unknown for them to plough up his garden.

The plot of this type is harder to summarise because the play is less structured, with episodes which do not always occur in the same order. The main characters are a Fool, a Farmer’s Man, a Lady, an Old Woman (‘Dame Jane’), an Adversary and a Doctor. Sometimes there is a Recruiting Sergeant and sometimes a Hobby Horse.

The basic action involves the wooing of the lady and the rejection of one suitor in favour of another. The Old Woman seeks the father of her illegitimate child. Two of the characters have a fight, and one is killed and then humorously revived by the Doctor.

The so-called HERO COMBAT PLAY is by far the most widespread with examples known in nearly every part of the country; including those already mentioned, where it can be found side by side with the other types.

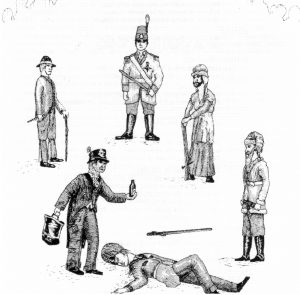

This play lacks a wooing element, and in its simplest terms consists of a Presenter, the vaunts or boasts of the Hero and his Adversary, a Fight, the Cure, and the ‘Quete’ or end-part where the players solicit the generosity of the audience.

The Hero is most commonly St. George, who has sometimes become King George or Prince George. Other heroes include Robin Hood and “Bullguize” (Bold Guizer?). The most widespread adversaries are Bold Slasher and the Turkish Knight, but a full list of all the names would be very long indeed. Oddly, there is very rarely a dragon. There is also the same sort of comic Doctor and humorous cure as in the Wooing Play.

As a short example, here is a Hero Combat play put together from lines common to many versions. [NB It is NOT a collected text]

FATHER CHRISTMAS [The Presenter]

In comes I, old Father Christmas, welcome or welcome not.

I hope old Father Christmas will never be forgot.

Room, room, give us room to rhyme

We come to show activity this merry Christmas time.

And if you don’t believe what I say

Step in, St. George, and clear the way.

GEORGE [The Hero]

In comes I, St. George, a noble knight.

I shed my blood for England’s right.

I am a mighty champion, a man of courage bold

And by my valour I won three crowns of gold

Where is the man that dare before me stand?

I’ll cut him down with my all-conquering hand

BOLD SLASHER [The Adversary]

In come I, Bold Slasher, come from Turkey Land.

I am the man that dare before you stand.

I’ll hack you and cut you as small as flies

And send you to the cookshop to make mince-pies,

St GEORGE

Then mind thy body and guard thy head

For with my sword 1111 leave thee dead.

[They fight.and Slasher falls]

FATHER CHRISTMAS

Oh Mercy, St. George, what hast thou done.

Thou hast slain my one and only son.

Is there a doctor to be found

To cure this man bleeding on the ground?

DOCTOR

In come I, the Doctor brave and good

And with my hand I can stop the blood

FATHER CHRISTMAS

How came you a doctor?

DOCTOR

By my travels.

I’ve been to Italy, Titaly, France and Spain

And now I’m back to cure the diseases of England again.

FATHER CHRISTMAS

What is your fee, Doctor?

DOCTOR

Ten pounds is my fee

But as you are an honest man,

Ten guineas I’ll take of thee.

I have a bottle by my side

It’s fame has spread both far and wide.

The stuff therein is called Elecampane.

It will bring the dead to life again

Here, Jack, take a sip from my bottle.

Let it run right down thy throttle. – Rise up now. [Slasher gets up]

BEELZEBUB

In come 1, Beelzebub

Over my shoulder I carry a club.

In my hand a dripping pan.

Please to give us all you can.

FATHER CHRISTMAS

A pint of your Christmas ale, sirs

Would make us merrily sing

But money in our box is a far better thing,

BIG HEAD

In come I that ain’t been yet

With my big head and little wit.

My head’s so big and my wit’s so small

I’ll sing a song to please you all.

he sings and all leave.

“Here, Jack, take a sip from my bottle.”

St George, a Hero-Combat play.

These plays are often elaborated with multiple adversaries, fights and cures, and with a procession of “supernumery” begging characters at the end.

In large areas of the North-Lancashire, Cheshire, parts of Yorkshire, etc., most of the plays show strong similarities of texts and characters. This is due to the influence of printed pamphlets or “Chapbooks”, the earliest known of which is about 1750.

The Hero-Combat Play has also spread to Wales, Scotland and Ireland, although it is confined mainly to areas of English influence. The Plays are ALWAYS in English, even though this may not be the first language of the performers. These countries have introduced their own characters into the play, for instance Scotland has Wallace and Galation (said to have been a leader of the Picts) and in Ireland, St. Patrick and Cromwell often occur. The play has been found even further afield, in Newfoundland for example.

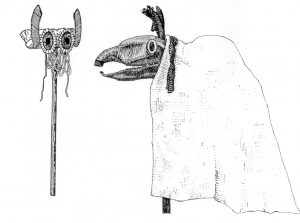

There are also a couple of minor plays or ceremonies which are not always regarded by scholars as folk plays at all, but which resemble them closely. They involve a strange sort of beast which originally consisted of an animal’s skull mounted on a short pole. The operator bends forward supporting his weight on the pole, and is covered by a cloth, thus creating a weird three-legged animal which can become the central character in a play.

A Tup and a three-legged Horse,

In East Derbyshire and the area round Sheffield this is a ram or ‘tup’ and is associated with the song “The Derby Tup. When no skull was available all sorts of ideas were usedto make a head of sorts out of a sack, a broom, etc.

“The Butcher that killed this Tup, sir,

He nearly lost his life”.

North and West of here there was a play of a similar kind with a horse called “Old Ball” and using the song “Poor Old Horse”. A Horse-ceremony (which was probably once independent) has become attached to the end of some “Souling” plays in Cheshire and also to some plays in Dorset.

WHEN IS IT PERFORMED?

“Good evening, ladies and gentlemen all

It’s Plough Monday makes Tommy so bold as to call.”

[Wooing Play Presenter]

“… this night we’ve come a-Souling good nature to find.” [song]

“…We’ve come a Pace-Egging and we hope you’ll prove kind.” [song]

To begin to understand anything about Folk Plays, they must be seen in their context as a calendar custom. This means that although the dates may vary between areas, a particular community always performs its play on the same day or days each year. Most commonly it is a Mid-Winter custom with the Sword Dance traditional to New Year or Boxing Day, and the date for the Wooing Play is Plough Monday which is the first Monday after twelfth night.

In most areas of the country the Hero Combat play is a Christmas custom and would be performed sometime during the weeks before and after. There are two important exceptions. In the North-West – Lakes, Lancashire and part of Yorkshire, the play has become attached to an Easter custom of begging for ‘Peace’ or ‘Pace’ eggs (originally Pache eggs) and is called Pace-Egging. In Cheshire it has become joined to a similar Halloween custom involving ‘Soul’ cakes and is called Souling. Sometimes Souling and Pace-Egging plays are treated as though they were separate types of play. This is not so – they are both classifiable as hero-combat, based usually on chap-book texts.

Quite a number of modern revivalist teams now ignore the seasonal aspect of the plays and perform throughout the year as the opportunity is offered.

WHO USED TO DO IT?

We are not London Actors – we travel the street.

We are not London Actors – we fight for our meat.

We are not London Actors who act upon the stage.

But we are just poor ploughboys who work for little wage.” [song]

“We’re none of the ragged sort but some of your finest kin.”

The players who took part in the Folk Play were people from the community in which they performed. Although they might go out to surrounding villages, they were not travelling players in the theatrical sense. The custom was usually a rural activity, although in Lancashire the existence of chapbooks helped people who were moving into the new towns to continue the custom, and it became widely practised there.

As shown on the back cover of this book there were many, many different titles given to the performers. One of the commonest was “Mummers” and this has lately become the name in widest use, with “Mummers’ Play” coming to mean any folk play.

Sometimes the performance of a particular play became the prerogative of a particular group – one family, or the workers at a particular farm. Teams whose title included the term “Plough…” did not necessarily have a Wooing Play. (The title “ploughboy” was often given to the horse-handlers who were the skilled elite of the farmers’ work-force.)

The ‘social class’ of the performers would probably vary with the aims of the performance. If the community benefited, for example, when candles called ‘plough lights’ were bought for the church, it was likely to attract people from higher up the social scale than a basic begging play which would have appealed to the very poor who really needed the money.

As a tradition declines so does the status of the people who perform it. In its last stages it is only children who keep it going. The Pace Egg play and the Tup play at least had reached this stage in many areas.

The slaughter of the 1914-18 war, the hard times which followed and the tendency during the twenties and thirties to despise anything ‘old-fashioned’, effectively killed off mumming and there are now very, very few teams who can claim to be ‘traditional’ in the sense that their play was handed down to them by a member of the earlier team. Amongst these must be numbered Antrobus Soulers (Cheshire), Chipping Campden Mummers (Worcestershire), Marshfield Paper Boys (Avon/Gloucestershire), Ripon Sword Dancers from Yorkshire (it is not a sword play) and Uttoxeter Feather Guizers (Staffordshire).

WHO DOES IT NOW?

“We’re one, two, three jolly boys all of one mind.” [song]

“We are the merry actors who show a pleasant play.”

It must be true to say that ninety-nine out of every hundred people who can claim to have seen a mummers’ play have been watching a revivalist team of recent formation.

The folk-song revival in the 1960’s and 70’s also generated interest in other ‘folk’ and traditional activities – including Mumming. The first of these new teams was probably Darlington Mummers formed from a folk-song club early in 1966 and Coventry Mummers (November 1966) was the first autonomous revival side with a full annual programme. Now the number of teams increases each year.

The approaches to texts, performance and costume vary widely between the strictly traditional who use local texts an their correct dates only, to teams who perform throughout the year, dress for effect and slant the performance towards entertainment. Often modern teams have a repertory of several plays of different types or origin.

WHY DID THEY DO IT?

“We wish you a merry Christmas and a happy New Year.

A pocket full of money and a cellar full of beer.

And a good fat pig in the pig-sty to last you all the year.”

“It’s your money we want, it’s your money we crave.” [Devil Dout]

“And we hope you’ll prove kind with your eggs and strong beer.” [song]

Speculation about the origins of the plays no longer seems fashionable in academic circles, but this is an area which still greatly interests he general public. Unfortunately it also involves the fewest facts and most guesswork. If you want a ‘ritual’ origin, the simplest argument might go like this-

Since earliest times death and regeneration has been apparent to man in his surroundings. The cycles of the Sun, the Moon, the Calendar, vegetation, animals and Man himself were so clearly important, that re-birth or resurrection has had a central place in many religions and ceremonies the world over. Its presence in the Folk Play, together with the seasonal nature of the, custom leads to the conclusion that the origins of the ceremony are ritualistic and “religious” insofar as the participants believed that they were influencing forces normally beyond their control. Even today people can have a vague feeling that there is some “luck” involved in which they can share by contribution to the collection – an attitude not discouraged by performers

Such customs are frequently the preserve of one sex only, and this one seems to have been confined to men; with one of them dressed as a woman (the Man/Woman or She-male) seemingly an important character.

It has been suggested that the three types of play originate from the same basic primitive ritual and represent different stages in its slow development through the centuries. The sword play which was common in Northern Europe and elsewhere could be the earliest form and the hero-combat play the latest. Plays having similarities with the wooing plays that have been collected in Northern Greece.

Obviously St. George cannot go all that far back in time and we do not know what characters the play had before his advent. Likely contenders are some of those who now appear rather oddly at the end of the play – the Sweeper, the She-male, the Man-with-the-Club-and-Ladle, etc.

hat is certain is that by the time good written records appear, the play had become no more than a “luck visit” that was valued for its ability to raise food, drink and money.

During the late nineteenth century the forces of respectability bore down heavily on “gross and unruly” activities such as mumming. Some teams relieved the pressure by become institutionalised and collecting solely for charity.

WHERE WAS IT PERFORMED?

“We knock at the door, we enter in

We hope your favour for to win.”

“Good Master and good Mistress, as you sit by your fire.”

“A room, a room; a roust, a roust

I’ve brought my broom to sweep your house …”

With the possible exception of the Sword Play which needs room for its dance, it seems that the earliest-known mummers took their play from house to house and farm to farm and would perform in the main living area…usually the kitchen. Before the Enclosures, isolated farms surrounded by their fields were much rarer than today, most of them being clustered into villages.

Later with smaller houses and changing attitudes to privacy the mummers started performing in public places – streets, pubs etc. Nowadays venues include concerts, dances and any other outlet which presents itself.

A team of mummers can vary in number from four to fourteen or more. A play can be as short as three minutes or longer than thirty. One of the governing factors would be the main outlets for performance. If a team is going from house to house in a village they want a short play – go in, do it, collect, get out and move on. The smaller the numbers involved, the greater is each individual share. If, however, they were tramping between isolated farms in mid-winter, the food, drink, warmth and company would be important and the plays might get longer with perhaps songs added as well. In the pubs and in the street, the entertainment value of the play could significantly effect the collection and might result in longer plays with more characters, extra fights and cures and perhaps a dancer or musician included.

If the collection was going to charity there would be no constraint upon numbers and the play might be expanded to include everyone who wanted to join in (cf. Minehead).

WHAT DID THEY WEAR?

“The next that comes in is Lord Nelson, you see

With a bunch of blue ribbons tied down by his knee

And a star on his breast like silver doth shine…” [Calling-on song]

“In come I, little Devil Dout

With my shirt-tail hanging out.”

“…And we’ve brought him along all dressed in his best

To see how he handles his sword.” [Calling-on song]

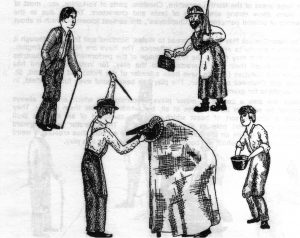

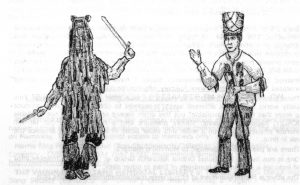

Among the costumes worn by existing teams may be found examples of several successive stages in development. Probably the earliest are made of strips of rag, attached by one end so that they hang and flutter, sewn thickly onto coat and trousers. Tall hats like large paper bags have strips which hang over the face of the wearer and conceal his identity (fig 5). The element of disguise is very important in early mummers’ dress and is the origin of the term ‘Guizers’ which is used in some areas as a name for the players. It has been suggested that this costume of “tatters” is in imitation of an earlier use of leaves etc., but there is no direct evidence for this.

This style of dress has also been made from strips of wallpaper, or strips of newspaper, etc. (Marshfield ‘Paper Boys’). Another probable development sees the rag strips reduced in quantity and become ribbons used for decoration. They were tied at knee, elbow, shoulder etc. and pinned onto shirts, when they sometimes became rosettes (fig 6). The hats often became very fine and in some places carried a good deal of the family wealth as chains, jewellery and watches, also small mirrors or bright things which were said to turn back the ‘evil eye’. Also found are shirts or smock-like coats decorated with patches – often random but sometimes cut out to the shape of animals etc.

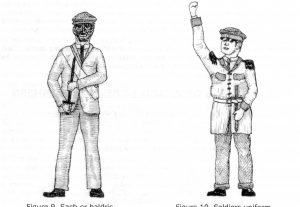

In the North-West a simple diagonal sash or baldric was worn over ordinary clothes (fig 7). jackets could be turned inside out – a popular disguise element, and possibly necessary when people had fewer clothes and styles were more distinctive – It is also reputed to render the wearer invisible to fairies. Shops which sold the chapbooks might also sell sets of different coloured sashes, and even “Real Iron Swords” – an Instant Pace-Egging Outfit.

In instances where the features were not hidden, disguise was often achieved by colouring the face. This was usually black (burnt cork or soot mixed with lard) but was sometimes red (sheep ‘raddle’ or brick-dust) or white or combinations of these.

In all these examples members of the team would have once dressed alike and there would have been no easy visual way to tell the characters apart. This is why so many speeches begin “In Come I…” – until told, the audience would not know which part was being played.

The idea of dressing to part would have come in by degrees. The first was probably the Man/woman who would want to be visibly female. The local doctor would have been a familiar figure and he may well have been the next to go over to realism. When a soldier was discharged, his only clothes would have been his old uniform, so soldiers’ red coats were not uncommon and would have been available for combatants (Fig 7) (cf Antrobus).

In the ‘theatrical’ revivals of the 1920’s and ’30’s, and in some of the more modern teams we see ‘dressing to part’ taken a stage further. St. George is once again a Crusader with a helmet, and often a shield which bears the same red cross as his surcoat. Turkish Knight is no longer a red-coated soldier with a straight sword and now has a turban and a scimitar.

Strips of rags. Rosettes.

Sash or Baldric. Sodier’s uniform.

WHERE CAN YOU FIND OUT MORE?

“If you don’t believe what I say…”

Since I first wrote this, three huge changes have radically effected people seeking information. The Internet, digitising and e-mail have made the acquisition and exchange of material much easier although much of it is only available through subscription-only sites. On the down side, the collapse of the Nett Book Agreement means private non-academics no longer have right-of-entry into University libraries and the like.

Instead of a detailing recommendhed books I have only to direct you to my Annotated Booklist on http://www.folkplay.info/Ron/Booklist.htm.

These books should be available through your local Inter-Library Loan Service. This usually works on several different levels. A request to obtain a book may produce the reply that it is “not available” but this often means only that it is not available LOCALLY. Repeated requests, steady pressure and a refusal to be put off will generate enquiries made on a wider and wider basis which will usually produce the book in time.

There are two websites devoted to Mumming matters.

One is run by the Traditional Drama Research Group at http://www.folkplay.info/ and includes a section with hundreds of links to other sites.

The other is MasterMummers at http://www.mastermummers.org/index.htm.

—AND MORE ——–

By now the reader with a casual interest in folk plays will hopefully have been satisfied, but there may be some who wish to take the study further. The books already quoted contain lists of references and suggestions for further reading, most of which can be found at one or more of the libraries listed at the back of this book.

My own Collection, now part of the Morris Ring Archive, has more material than is publicly accessible anywhere else. Although not specifically collecting texts, I still have a mixed bag of over 750. Any serious enquirer may view it in Coventry by arrangement, and I can handle simple queries by post, phone or e-mail.

TO PRACTISING OR WOULD-BE REVIVAL MUMMERS

Texts If you are looking for texts from a specific locality you should first consult the Geographic Index (see book list and now on line). You may find materials in your “Local Studies Centre” or County Archives. A lot of the older Archives do not reference folk plays under “Folklore” or “Drama” etc. but under the names of the villages from which they came. This can involve you in some digging, but if you find something you should take steps to see that it is not lost again.

If you have no luck and cannot get to one of the Libraries listed. might help you or put you in touch with some local specialist. They are also the people to contact if you become interested in collecting, – they give advice and collate everybody’s findings. If you do come across any previously unknown text or detail you should document it as completely as possible and at the very least put a copy in your local archives. This can benefit you as a researcher, as Archivists treat you a lot better if you are contributing to them. Ideally you should send copies to the Vaughan Williams Library, and the Morris Ring.

If you are already in a Men’s Mumming Team your club should consider joining a group such as the Morris Ring, which accepts mummers. You will be put on their address list, you will receive all their literature etc. and, most importantly, you will be covered by their insurance against third-party claims. SOME SUCH COVER IS VITAL.

Other organisations which provide cover are the Morris Federation and the Open Morris.

© R.Shuttleworth 1984/2011. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the author.